Police1 recently completed a survey of U.S. law enforcement officers on work scheduling. The response was remarkable. With very little promotion, over 1,000 working cops completed the survey and the respondents were forthright about the schedules they work.

Thank you for reading this post, don't forget to follow and signup for notifications!

Demographics of the sample

Both the tenure and the ages of the respondents fit a nearly perfect bell curve. About 10% had either under five years or over 30 years of experience, with 38% in the 11-20 year range. Consistently, 35% were 35-44 years old, with 23% 25-34 years of age and 14% over 55. This was a true cross-section of American policing.

Most (44%) were line cops, with the title of officer, deputy, or trooper. Twenty-nine percent were first-line supervisors, 11% were lieutenants, and 16% executive-level officers or detectives. Fifty-four percent worked an urban or suburban beat, with 14% working in a rural area, and 32% having a mixed coverage area. Eighty-three percent worked for a municipal police or sheriff’s department. Four percent were state police/patrol officers, 7% worked for a campus police department, and the remainder were employed by a proprietary (school, hospital, transit, etc.) or tribal police department or a federal agency.

Forty-six percent were patrol cops. Eleven percent worked in investigations, and 16% were line supervisors. The remainder worked in correctional or administrative roles. Over half (53%) worked for agencies with 10-100 sworn officers. Twenty-seven percent worked for outfits with 100-499 cops, and 5% worked at agencies with fewer than ten officers. Only 15% were employed by large agencies with more than 500 officers.

The officers’ working schedules were distributed fairly evenly:

Some officers shared unusual or mixed schedules that don’t fit standard categories:

- 8 hours a day plus overtime for sporting events usually 60-75 hours weekly

- 8.25 hour shift, rotating early shift/late shift (1 hour early or normal time), 4 days on 2 days off

- 5 on/2 off; 5 on/3 off; (4) 8.5 hr shifts and (1) 9 hr shift

Most of the cops were reasonably happy with their schedules, although there were some significant dissenters:

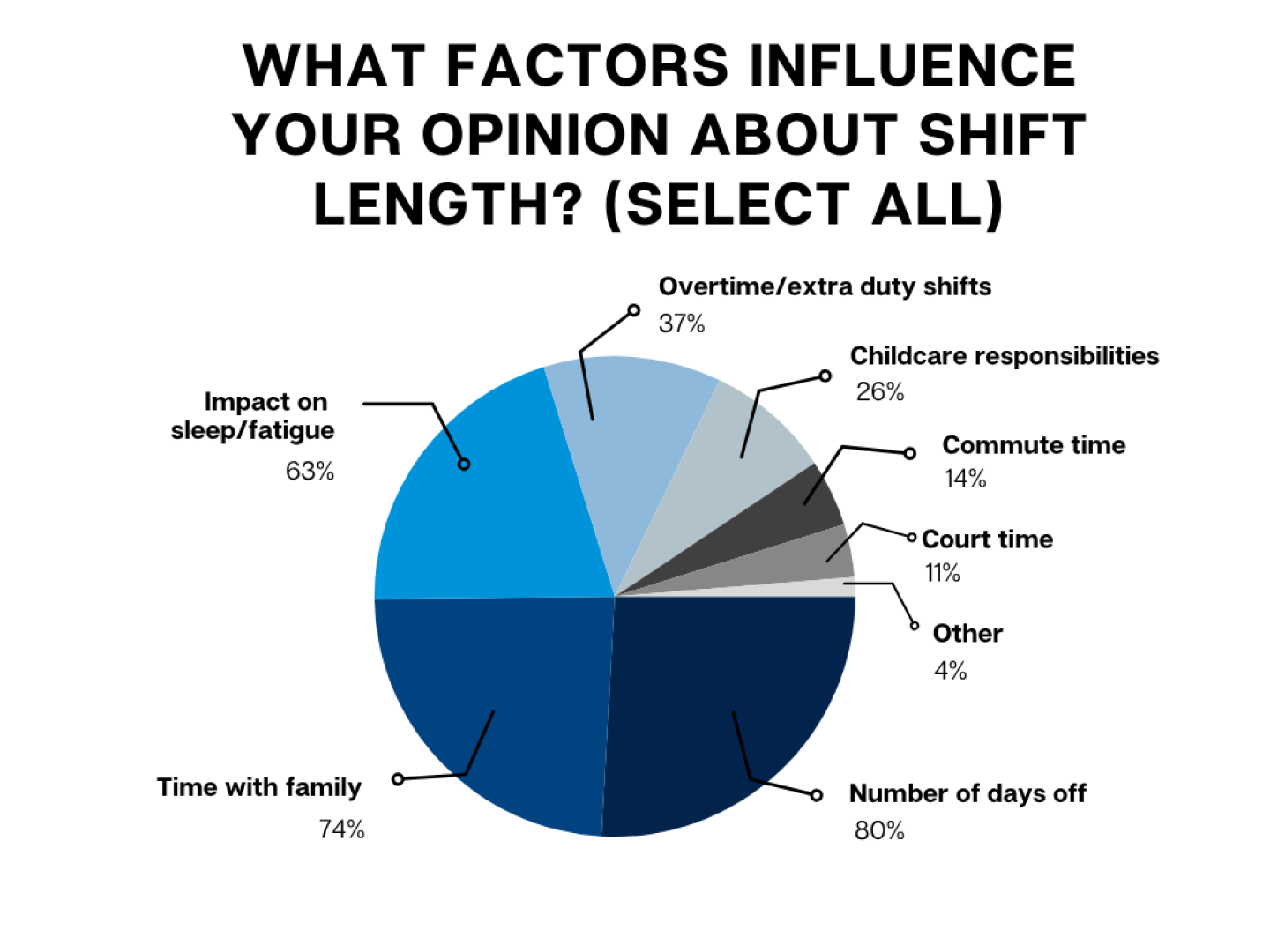

Time off was the largest influence on schedule satisfaction, with over 80% citing this as a concern. Seventy-four percent were troubled about the time available to spend with their family, and 63% cited the impact on sleep and fatigue as a consideration. Other factors were overtime and extra duty shifts (37%), childcare responsibilities (26%), time spent in court (11%) and commute time (14%). This was consistent with the What Cops Want in 2024 survey, where fatigue, interruptions to sleep patterns, and lack of time for self-care and exercise were key issues.

Here’s what officers had to say in this survey:

We work 10 hour shifts but the rotating days off sucks.

Predictable schedule, every other weekend is 3 days off.

Shifts overlap, so you almost never get held over by a late call.

We were on 3 13-hour shifts, 4 days off. It was great! Now with 4 10-hour shifts, rookies are calling off all the time? Short staffed?

Flexing and voluntold is bad for business. The best way to ruin people is to hire them for one job, then make them do three others. Old methods of “I did it so can you” supervision are outdated and dysfunctional.

The ideal shift duration

Asked what shift they would most like to work, 10 hours was the overwhelming choice, with half of respondents choosing this:

Officers were evenly divided on whether their work schedules affected their health. Thirty-three percent said it had a positive influence, 33% said it affected them negatively, and 22% thought their working hours had no impact. Eleven percent weren’t sure.

Work schedules don’t change much. Only 14% said they had moved to longer shifts in the last three years, while 10% moved to shorter work hours. Eight percent adopted a rotating or hybrid schedule. Sixty-seven percent had been on the same work schedule for at least the last three years.

Although about a quarter of respondents prefer 12-hour shifts, they were among the most criticized in the comments. In a perfect world, an officer can go home after 12 hours, get some sleep, maybe work out, eat and attend to personal hygiene before going back to work. But the police officer’s world is seldom ideal. Smaller agencies don’t have enough flexibility to accommodate people calling in sick, court appearances, and other unplanned holes in the duty roster.

Officers can be held over to cover for absences in the next shift, so the 12-hour day becomes a 16- or 18-hour day, leaving barely enough time to eat and shower before they’re back in the saddle. Add in a commute between the duty station and home, and the officer might as well be working 36 hours straight, with the possibility of being held over again. When back-to-back holdovers stack up, the math becomes brutal. Subject someone to a few of these duty tours, and you have an armed zombie.

I started with 8-hour shifts 30 years ago and I loved them, but I loved everything about the job then. Went to 10-hour shifts and that seemed just right to get work done and still have a good amount of time off. Twelve hours are too long and too hard on an old body. The “every other weekend” off is no good when every weekend you work is when family things are happening (kids’ games, birthdays, etc.).

As someone who started working 8-hour shifts, 5 days a week on night shift, I see the benefits of 12-hour shifts. The consistency of the schedule with 5 days off one week and ensuring every other weekend off is a pro to family relations. However, as a supervisor, I think 12-hour shifts have created more idle and less driven police. When coming to work for 8 hours, the urge to be proactive is stronger and results in more drive, vs. the 12-hour shift, where the mindset is, let’s sit back and see what today brings. Twelve hours is a long time to stay in a heightened sense of awareness.

Doubling up staffing to facilitate training

These schedule stresses become more complicated when agencies try to build training time into already tight staffing models.

Some agencies, especially those on ten-hour shifts, have a four-day work week with one day per week double-staffed. This is supposed to allow half the workforce to attend training, firearms qualification, or some other duty outside their normal schedule, but it usually doesn’t work out. Unless there is a dedicated training function that can organize and present training every week, with a minimum of two weeks to get eight or ten hours of training to everyone, the department winds up with twice as many cops at roll call. Sometimes officers have to double up because of a shortage of patrol cars. This can be a plus, but it’s usually wasteful and inefficient.

There is also the problem of scheduling the training. Trainers, especially those assigned to the function full-time, tend to be day-shifters. If they don’t flex their time to put on classes during the hours patrol officers are normally scheduled to work, the time between the end of the training day and the start of the next patrol shift may not be enough to allow rest and attention to personal needs. If the class goes during the trainer’s regular workday of 0800-1700, the cops they’re training may have only four or five hours before they’re expected in pre-shift briefing. The result is a schedule that looks functional on paper but leaves officers more exhausted than prepared.

Twelve-hour shifts don’t leave any time to rest when dealing with late calls. Also, court during your off time makes it dangerous for you during your work hours. I’m not talking about days off. It’s the time in between shifts.

The only benefit of a 12-hour shift is having every other weekend off.

While the 12-hour Pittman schedule offers every other weekend off, my opinion as an older veteran officer is that 12 hours in this uniform and in the squad is too long. It causes medical issues due to the mere weight we carry, both physical and emotional.

Shiftwork schedules that look good on paper may not allow for assignments outside of regular duty hours. The officer working the night shift who is called into court the day before or after his shift is not going to get adequate rest before being expected back at work. This is tolerable (though still dangerous) if it’s an occasional thing, but the nature of the work the officer does may mean a lot of court appearances. This is especially true of officers who work traffic or DUI enforcement, which often results in an excess of people challenging tickets or arrests or demanding administrative hearings over the suspension of their driver’s licenses.

Managing off-duty intrusions

Having most of the criminal justice system working Monday-Friday, 0800-1700 means the night shift cop will be the odd one out. Court appearances, pre-trial conferences, and simple, “See what Joe thinks about that” calls come during the day, when Joe is trying to sleep. Although these people know what hours Joe works, they conveniently forget when they’re dialing the phone. This is especially true when dealing with a non-cop who has never had to work a round-the-clock schedule or an admin type who has been on a business hours schedule for more than ten years.

This reiterates something from the 2025 What Cops Want survey: street officers frequently view their leadership as out of touch because they refuse to suit up and get back to the tools now and then. A chief executive or senior manager with long tenure might have been in law enforcement longer than some of their cops have been alive. They certainly did not know the chief when he was a patrolman, and they may have difficulty even imagining him in that role. The chief or senior executive may believe they understand the dynamics of working the street, but they may not understand how things have changed or that they lack credibility because of their detachment. That disconnect becomes especially sharp when leaders make schedule decisions that affect rest, safety and family time.

One reliable way to rebuild trust around scheduling decisions is for leaders to share the realities of the job again. When younger troops see the old man in the same Class B uniform they’re wearing, climbing into a car with an FTO (it is unwise to try this alone if you’ve been in the office for a while), and working each of the duty shifts a few times a year, confidence and trustworthiness soar. The chief is also likely to find this a revelatory experience and will see the job their cops are doing from a whole new perspective.

This reinforces a principle many chiefs and sheriffs may have forgotten. They manage their departments and promote subordinates to be managers. This works well enough when the things being managed are inanimate, like patrol cars, training ammunition, and radio batteries. However, you have to lead people. Management and leadership are not the same thing.

In these days of chronic understaffing, when recruiting is more of a challenge than ever before, making the most efficient use of personnel resources is critical. Besides the need to use personnel time effectively, management must ensure their officers, deputies, and troopers are cared for, given adequate time to rest and exercise, and are not overextended. Failing to do so doesn’t just make for a tired cop, although that’s a major consideration. It can make for a depressed, anxious, or otherwise unhealthy cop, one who has less job satisfaction and is looking to improve their lot by switching careers. Every badge who walks out the door takes with them their experience and the investment the agency made in recruiting and training them. It also means the department has to spend even more money to replace them, drawing from an ever-shrinking pool of often inferior candidates.

Shift schedule trends at a glance

Taken together, the survey results point to several trends shaping how agencies think about schedules today:

- 12-hour shifts are now the most common, with more than one-third of officers working them, yet only about a quarter prefer them.

- 10-hour shifts are the clear favorite, preferred by nearly half of respondents and viewed as the best balance of time off and daily workload.

- Satisfaction is split — just over one-third are very satisfied with their schedule, while nearly the same share report dissatisfaction or negative health impacts.

- Sleep and fatigue are major pressure points, with more than 60 percent saying shift length affects rest and recovery.

- Family time remains a top driver, shaping opinions on ideal shift length and preferred days off.

- Two-thirds of agencies have not changed schedules in the last three years, even as staffing shortages and burnout continue.

- Mixed and rotating schedules are widely disliked, with many officers citing unpredictable sleep, family disruption and difficulty planning around rotating days or nights.

- Officers strongly value more consecutive days off, even if it means longer workdays.

- Health impacts are balanced — roughly equal numbers say their schedule helps or harms physical and mental well-being.

Tactical takeaway

Audit your agency’s scheduling practices to ensure shifts promote both productivity and wellness. Balance operational needs with rest, training, and family time to prevent burnout and attrition.

What strategies has your agency used to improve officer scheduling and work-life balance? Share below.